In this blogpost on the Sine-Saloum Delta, Senegal, I try to work out how deltaic flows do not necessarily follow the bounded, unidirectional paradigm of the politically, geographically or hydrologically mapped delta – be it in a hypersaline inverse estuary like the Sine-Saloum Delta, where more seawater flows inland than freshwater outwards to the coast, or in any other (non-inverse) delta. Rather than the delta and its flow, there exist(ed) a multitude of deltas and flows, relating to individual outward and inward movements via certain gateways. The Sine-Saloum Delta might appear peripheral, bounded and unidirectional in a mainland- or birds-eye-view, yet delta inhabitants have always been actively making (use of) different flows and traversing the delta, enlarging it and bending our understanding of what the delta is. However, their striving for mobility also highlights today's growing restrictions of such agentive movement due to political and economic forces and people's increasing dependencies on what comes from the outside of the delta.

Beyond the delta

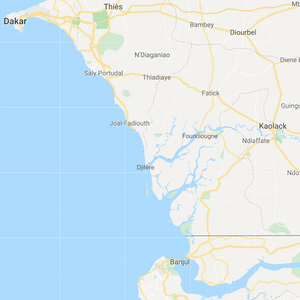

The Sine-Saloum Delta is surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean in the West, Senegalese mainland in the North and East and Gambian mainland in the South. Over time, these surroundings were in change and so was the delta. The Senegambian monoliths (erected between the 3rd Century BC and the 16th Century AD) that stretch from North-East or above the delta to the Gambia River indicate the past existence of a common societal sphere across the region. Later, the North and East were dominated by (migrant) Serer groups (from at least the 13th Century on) and the South by Manding groups, before the national boundaries were defined by colonialists. In the delta itself, shell middens (accreted since up to 5000 years ago) are probably traces of a predecessor culture to today's inhabitants while today's villages date to between the 8th and the 18th century.And so Suleyman Fall said: "We are not just from here. We were always migrants."

Indeed, the Serer Niominka, today scattered across 19 islands, were and are highly mobile, cosmopolitan, egalitarian and diverse. They stem either from a Serer migrant group that was 'Mandinkized' from the South or from Manding, Jola or Bak groups who were 'Sererized' from the North. They were and are go-betweens who travelled and reached out while neither establishing a system with centralised power among themselves nor being easily reached and controlled by others: they remained only partially in contact with and under the rule of the two Serer Kingdoms Sine and Saloum (East and North) and the Manding kingdom of Niumi at the mouth of today's Gambia River (South), and they got Islamised from the Manding Gambia region only in the second half of the 19th Century. Furthermore, Portuguese colonial explorers in the 15th Century could not penetrate the delta from the coast (West) because of the fierce resistance of its inhabitants, and the French colonial administrators 'governed' the delta from Foundiougne, a terra-firma-town half-way to Kaolack (North-East). The French established the shipping route to Kaolack, one of West Africa's biggest markets and an important region of salt and peanut production, through the delta, but exercised only limited control over the people in the delta.

For the Serer Niominka themselves, their main routes of relation, trade and travel away from their individual islands and its surroundings pointed North-East towards Kaolack and South down the coast. They undertook fishing campaigns and transported and traded goods such as salt, dried fish, molluscs, millet or rice as far as Sierra Leone. Almost half of the year they were not 'home' but facilitated the coast-to-Transsahara-trade and connected the coast as well as Southern places with the Senegalese inland – until the 1930s by the means of dugout canoes and from then on with a type of boat that could hold more than 20 tonnes.

Shifting Nodes

For most of the 20th Century, the central node for entering and leaving the delta from Senegalese terra firma was Kaolack, situated beyond the delta at the upper part of the Saloum river. There was a whole quarter built by delta-born people. And older women remember how they drove up to Kaolack to sell tissues, palm-oil or molluscs and, in turn, buy goods such as soap or iron pans, while older men narrate how they shipped tons of mangrove wood and shells for construction there. Before motorisation slowly setting in at the beginning of the 1950s, many of their voyages were bound to the paddle and the sail and took days.

The other central node for the Serer Niominka, Banjul, lied down the coast on Gambian terra firma. In 1938, the French explorer Lafont noted that the coastal villages of the delta are 'far from the continent', yet, for the delta inhabitants, the mainland, albeit Gambian, was actually easy to frequent. For example, in the mid 20thCentury, the Serer Niominka organised the transport of peanut on the Gambia River down to the factory in the capital. Or they cut the wood for their pirogues in the forests along the river and traded goods, making use of the arbitrary border and the different currencies. Furthermore, many families today have members who live across the border and women as well as men went to work as seasonal labourers in Banjul, just like they did in Kaolack or Dakar.

Also towards Dakar, the centralist capital, first of the French colony and later of the independent Senegal, people indeed did travel and relocate, both temporally and indefinitely. But the sea-travel was long, there was no gateway-village, no direct overland road, and consequently not much direct circulation of people and goods. Thus, while the Southern margin of the delta has always been a gateway, the opening of the Northern margin took much longer.

What supported the secludedness of this side and at the same time served as the ideational 'point of departure' of the Serer Niominka was the spit of Sangomar that reached from the North and ended before the Southern part of the Delta. Here, their 'founding mother,' on her long journey of searching for a new homeland, had landed and chosen to move 'up' the delta. And beyond here lied the 'other'.

Sangomar kept away the ocean and calmed the waters, endowed meaning, orientation and identity, structured the colonialists' shipping routes upstream and separated the inhabitants of the delta from the Lebous, a highly mobile community of skilled fishers with their home-base in today's Dakar. They would fish beyond Sangomar and up the coast. The Serer Niominka, in turn, when not on fishing campaigns down the coast or in the mangroves, would fish close to their individual villages while abstaining from another village's fishing grounds. The exploitation of the serpentine estuaries of the delta were largely tied to villages or even individual people who were known for frequenting them, whereas transport on them was open to all.

When Senegal became an independent state in 1960, the nationalisation program rendered all lands and waters, hence also the estuaries, public property. Confiscating someone's net because he fished within someone else's waters was not possible any more. Then, in 1980, the first dirt-road was built to the then fish factory in Djifère, connecting Dakar via Mbour and Joal with the delta. And in 1987, the spit of Sangomar broke in a storm surge. Sangomar turned into an island and the delta lay bare.

With the waters nationalised, the road built, and Sangomar broken, Djifère grew into a village at the tip of the mainland, in the place were Sangomar broke. It became a departure point of Lebou fishing at the delta's coast and in the estuaries, and the trading centre for them and the Serer Niominka. Today, it is the main gateway in and out of the Delta. Through here flow all kinds of goods out of and into the Delta. And from here many couriers, regular boat-buses, take off.

Banjul in turn has remained of certain importance, especially for buying cheap products, while Kaolack and the waterway towards it have widely lost their relevance for the delta inhabitants or those who want to access them.

Shifting Mobilities

As these developments through time show, on the one hand, the Sine-Saloum Delta's inhabitants with their movements in and beyond the delta rendered it something more than itself. On the other hand, also other ideas, practices, goods and people always flowed into the delta from different places and sides to a certain degree and in various time-frames. More recently, however, the balance of agentive, circular in-out movement of the inhabitants and inflow has been undergoing profound change.

"A border is something where you cannot cross. We Niominka did not know borders. The world laid open and we were curious. But today there are borders which we cannot easily cross, while many things easily reach us," Suleyman Fall added. The tightening of all country borders South and North, the shift towards road transport away from the coast and around the delta, the advancement of a (state advocated) common deltaic, instead of individual insular, identity, the governmentalisation of space (often in the name of conservation), the sprawling of Djifère as a trading hub at the doorstep, or the growing demand and increasing inflow of consumer goods, which partly substitute crops that cannot be grown any more due to heightened salinity and drought – all this decreases the Niominka's circular movements beyond the Delta while increasing the inflow. The delta's boundaries thus become more permeable for some (especially goods) and less permeable for others (especially people). The fishing, trading and transporting routes of the Niominka that allowed for variability, individuality and cosmopolitan participation are decreasing and the delta is becoming increasingly inflowing and fixed – not necessarily in geographical or hydrological, but rather in social, political and economic terms. Or, in other words, while historically, the Serer Niominka were always moving towards the world, now the world is increasingly moving towards them. And while their circular mobility generally decreases, those who want to move have to reach beyond (closed) borders and embark on longer, riskier and more terminal trajectories.

Note: The name Suleyman Fall has been changed for the sake of anonymity.

Literature:

Cormier-Salem, M. C. 1999. Rivières du Sud: sociétés et mangroves ouest-africaines, vol.1. IRD.

Hardy, K.; Camara, A.; Pique, R.; Dioh, E.; Guèye, M.; Diadhiou, H. D.; Faye, M.; Carré, M. 2016. Shellfishing and Shell Midden Construction in the Saloum Delta, Senegal. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 41, 19–32.

Klein, M. A. 1968. Islam and imperialism in Senegal: Sine-Saloum, 1847-1914. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Lafont, F. 1938. Le Gandoul et les Niominkas. C.E.H.S.A.O.F.1., TXXI, 385-450.

Picture source: googlemaps https://www.google.com/maps/@14.0083101,-17.1075559,9z