Along the Kemi River in Finnish Lapland, people frequently refer to places as being 'higher' or 'lower' and of moving 'up' or 'down', although the terrain is rather flat. These directions and orientations resonate with the main direction of the river's flow, and with how this flow figures in people's memories and place names. This article illustrates how stories and experiences of river travel and transport can shape space.

The article introduces the term 'fluvitory' to de-centre the primacy of a 'territory' imagination, where the ground is seen as fundamental, and rivers and water flows as secondary features; instead, a fluvitory perspective begins by following the rivers - as did the people of the Kemi River basin - and opens up the land from the the river bank onwards.

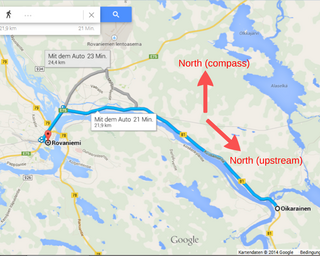

Along the Kemi River, the fluvitory perspective also equates 'upstream' with 'north', which again resonates with a host of experiences and centre-periphery relations in Lapland.

Thinking the fluvitory further, into the lifeworlds of delta inhabitants rather than river dwellers, may become an in interesting challenge for the DELTA project. What happens to the fluvitory, if there is no significant main direction of the current? What happens if this main current changes directions twice a day? Where is up and down then?

You can access the article online.

A short excerpt from the article:

The host of everyday activities in which people have been engaging along the riverbanks have shaped a clear understanding of ‘up’ and ‘down’ according to the river’s flow. When washing laundry, cutting hay or simply watching the water’s currents in summer or the passing of ice floes in spring, generations of river dwellers have perceived the dominant direction of movement. Living and working on the river, in short, meant dwelling not just in a world of flows but in a world flowing into a particular direction. Because both travel routes and settlements were concentrated along the rivers, these watercourses served as crucial organisers of the river dwellers’ world. As people and things came and went along the river, and many activities were tied to its waters, people’s geography must have resembled more a ‘fluvitory’ of rivers, tributaries and brooks than a territory, a plane crisscrossed by rivers and dotted with hills.

I propose the term fluvitory for two reasons: first, it points to a specific aspect of Oslender’s ‘aquatic space’, namely, the space-making capacities of people’s encounters with the rivers’ currents. Albeit heterogeneous, these currents along the Kemi River are largely unidirectional, materialising a poignant differentiation between upwards and downwards. Second, the term fluvitory is to unsettle the implicit bias of ‘territory’ towards terra firma, and thereby contributes a concrete proposition to the recent calls for more ‘wet’ and less ‘terrestocentric’ approaches as outline above. Territory is often associated with land or terrain, which have a solid and passive ring to them even when dubbed as property and military stage, respectively. By foregrounding fluvial dynamics, my proposition also differs from recent conceptualisations of ‘hydrosocial territory’, which aim at understanding territorialisation through a political ecology approach to water control.

Introducing the fluvitory term is not to re-inscribe an opposition between water and land, but to shift our way of understanding space as formed not only by terrestrial activities and stories set on passive ‘terrain’ or ‘land’ but also by fluvial ones, set within the movements of a world of currents and eddies. Of course, also ‘river dwellers’ live on the land, herd land-based reindeer, manage forest on dry land and mostly drive on solid roads. However, approaching their lifeworlds as a fluvitory does not privilege solid land as primary, which would see riverine flows as secondary add-ons to a generally fixed territory. Rather, it starts with the rivers’ currents, as do many traditionally significant activities along the Kemi River, and relates them to the land.